- Home

- M. R. Carey

The Book of Koli

The Book of Koli Read online

Copyright

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2020 by Mike Carey

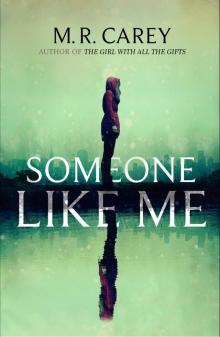

Excerpt from Someone Like Me copyright © 2018 by Mike Carey

Excerpt from Annex copyright © 2018 by Rich Larson

Cover design by Lisa Marie Pompilio

Cover photography by Blake Morrow https://blakemorrow.ca/

Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Orbit

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

orbitbooks.net

First Edition: April 2020

Simultaneously published in Great Britain by Orbit

Orbit is an imprint of Hachette Book Group.

The Orbit name and logo are trademarks of Little, Brown Book Group Limited.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019948411

ISBNs: 978-0-316-47753-6 (trade paperback), 978-0-316-47747-5 (ebook)

E3-20200304-JV-NF-ORI

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Acknowledgements

Discover More

Extras

Meet the Author

A Preview of Someone Like Me

A Preview of Annex

Also by M. R. Carey

Praise for the Novels of M. R. Carey

For AJ

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

1

I got a story to tell you. I’ve been meaning to make a start for a long while now, and this is me doing it, but I’m warning you it might be a bumpy road. I never done nothing like this before, so I got no map, as it were, and I can’t figure how much of what happened to me is worth telling. Monono says I’m like a man trying to cut his hair without a mirror. Too long and you might as well not bother. Too short and you’re probably going to be sorry. And either road, you got to find some way to make the two sides match.

The two sides is this: I went away, and then I come home again. But there’s more to the story than that, as you might expect. It was a hard journey, both ways. I was tried and I was tested, lots of times. You could say I failed, though what I brung back with me changed the world for ever. I met the shunned men and their messianic, Senlas, who looked into me with his hundreds of eyes. I crossed the ruins of Birmagen, where the army of the Peacemaker was ranged against me. I found the Sword of Albion, though it was not what I was looking for and it brung me as much harm as good. I fought a bitter fight against them I loved, and broke the walls that sheltered me so they’d never stand again.

All this I done for love, and for what I seen as the best, but that doesn’t mean it was right. And it still leaves out the reason why, which is the heart of it and the needful thing to make you know me.

I am aiming to do that – to make you know me, I mean – but it’s not an easy thing. The heft of a man’s life, or a woman’s life, is more than the heft of a shovelful of earth or a cord of timber. Head and heart and limbs and all, they got their weight. Dreams, even, got their weight. Dreams most of all, maybe. For me, it seems dreams was the hardest to carry, even when they was sweet ones.

Anyway, I mean to tell it, the good and the bad of it all together. The bad more than the good, maybe. Not so you can be my judge, though I know you will. Judging is what them that listen does for them that tell, whether it’s wanted or not. But the truth is I don’t mainly tell it for me. It’s rather for the people who won’t never tell it for themselves. It’s so their names won’t fall out of the world and be forgotten. I owe them better, and so you do. If that sounds strange, listen and I’ll make it good.

2

My name is Koli and I come from Mythen Rood. Being from there, it never troubled me as a child that I was ignorant what that name meant. There is people who will tell you the rood was the name of the tree where they broke the dead god, but I don’t think that’s to the purpose. Where I growed up, there wasn’t many as was swore to the dead god or recked his teaching. There was more that cleaved to Dandrake and his seven hard lessons, and more still that was like me, and had no creed at all. So why would they name a village after something they paid so little mind to?

My mother said it was just a misspeaking for Mythen Road, because there was a big road that runned right past us. Not a road you could walk on, being all pitted stone with holes so big you could lose a sheep in them, but a road of old times that reminds us what we used to be when the world was our belonging.

That’s the heart of my story, now I think of it. The old times haunt us still. The things they left behind save us and hobble us in ways that are past any counting. They was ever the sift and substance of my life, and the journey I made starts and ends with them. I will speak on that score in its place, but I will speak of Mythen Rood first, for it’s the place that makes sense of me if there’s any sense to be found.

It is, or was, a village of more than two hundred souls. It’s set into the side of a valley, the valley of the Calder River, in the north of a place called Ingland. I learned later that Ingland had a mess of other names, including Briton and Albion and Yewkay, but Ingland was the one I was told when I was a child.

With so many people, you can imagine the village was a

terrible big place, with a fence all round it that was as high as one man on another man’s shoulders. There was a main street, called the Middle, and two side streets that crossed it called the Span and the Yard. On top of that, there was a score of little paths that led to this door or that, all laid with small stones trod down until they was even. None of the houses was built within fifty strides of the fence. That was Rampart law, and never broke.

I’m Koli, like I already said. Koli Woodsmith first, then Koli Waiting, Koli Rampart, Koli Faceless. What I am now don’t really have a name to it, so just Koli. My mother was Jemiu Woodsmith, that was Bassaw’s daughter and had the sawmill over by Old Big-Hand stream. I was raised up to that work, trained by Jemiu how to catch wood from a live tree without getting myself killed, how to dry it out and then steep it in the poisonous soup called stop-mix until it was safe, and how to turn and trim it.

My father was a maker of locks and keys. I am dark brown of skin, like he was, not light like my mother and my sibs. I don’t know what my father’s name was, and I don’t think my mother knowed it either, or if she did she never told me. He journeyed all the way from Half-Ax to put new locks on the doors of Rampart Hold, and he was billeted for the night in my mother’s mill. Two things come of that night. One of them was a brand-new lock on our workshop door that would stand against the end of the world. The other one was me. And there’s at least one of the two my mother never had no cause to regret.

So my mother and my father had just the one night of sweetness together, and then he went back home. Half-Ax being so far away, the news of what he had left behind him probably never got there. Or if it did, it didn’t prompt him to return. I come along nine months after that, dropping out of Jemiu’s belly into a big, loud, quarrelsome family and a house where sawdust settled on everything. The sound of the saw turning was my nursery song, you could say, and my alarum too. The fresh-cut wood was stacked in the yard outside the house so it could dry, and the stacks was so high they shut out the sun at noon-day. We wasn’t allowed to go near the piles of fresh wood, or the wood that was steeping in the killing shed: the first could strike you down and the second could poison you. Rampart law said you couldn’t build nothing out of wood unless the planks had steeped in stop-mix for a month and was dead for sure. Last thing you wanted was for the walls of your house to wake up and get to being alive again, which green wood always will.

My mother had herself five children that lived to be born, a thing she managed without ever being married. I heard her say once that though many a man was worth a tumble, there wasn’t one in a hundred was worth living with. I think it was mostly her pride, though, that got in the way of her marrying. She never liked much to pull her elbows in, or bow to another’s will. She was a fierce woman in all ways: fierce hard that she showed on the outside; fierce loving underneath that she mostly hid.

Well, the mill did well enough but it was not a Summer-dance and there was times when Jemiu was somewhat pressed to keep us fed. We got by though, one way and another, all six of us bumping and arguing our way along. Seven of us, sometimes, for Jemiu had a brother, Bax, who lived with us a while. I just barely remember him. When I was maybe three or four Summers old, he was tasked by the Ramparts to take a message to Half-Ax. He never come back, and after that nobody tried again to reopen that road.

Then my oldest sister Leten left us too. She was married to three women of Todmort who was smiths and cutlers. We didn’t get to see her very much after that, Todmort being six miles distant from Mythen Rood even if you walk it straight, but I hoped she was happy and I knowed for sure she was loved.

And the last to leave was my brother Jud. He went out on a hunting trip before he was even old enough to go Waiting, which he done by slipping in among the hunters with his head down, pretending like he belonged. Our mother had no idea he was gone. The party was took in the deep woods – ambushed and overwhelmed by shunned men who either would of et them or else made shunned men out of them. We got to know of it because one woman run away, in spite of getting three arrows in her, and made it back to the village gates alive. That was Alice, who they called Scar Alice after. They was not referring to the scars left by the arrows.

So after that there was only me, my sisters Athen and Mull, and our mother. I missed Leten and Jud very much, especially Jud because I didn’t know if he was still alive and in the world. He had been gentle and kind, and sung to me on nights when we went hungry to take my mind away from it. To think of him being et or eating other people made me cry sometimes at night. Mother never cried. She did look sad a while, but all she said was one less mouth to feed. And we did eat a little better after Jud was gone, which in some ways made his being gone worse, at least for me.

I growed up a mite wild, it’s got to be said. Jud used to temper me somewhat, but after he was gone there wasn’t nobody else to take up that particular job. Certainly my mother didn’t have no time or mind for it. She loved us, but it was all she could do to keep the saw turning and kill the wood she cut. She didn’t catch all the wood herself, of course. There was four catchers who went out for her from November all the way through to March, or even into Abril if the clouds stayed thick. This was not a share-work ordered by the Ramparts, but an agreement the five of them made among themselves. The catchers was paid in finished cords, one for every day’s work, and Jemiu paid them whether the day’s catch was good or bad. It was the right thing to do, since they couldn’t tell from looking which wood was safe and which was not, but if the catch was bad, that was a little more of our wood gone and nothing to show for it.

Anyway, Jemiu was kept busy with that. And my growed-up sisters Athen and Mull helped her with it – Athen with good grace; Mull with a sullen scowl and a rebel heart. I was supposed to do everything else that had got to be done, which is to say the cooking and the cleaning, fetching water and tending the vegetables in our little glasshouse. And I did do those things, for love and for fear of Jemiu’s blame, which was a harder hurt than her forbearing hand.

But there was time, around those things, to just be a child and do the exciting, stupid, wilful things children are bound to do. My best friends was Haijon Vennastin, whose mother was Rampart Fire, and Molo Tanhide’s daughter that we all called Spinner though her given name was Demar. The three of us run all over Mythen Rood and up the hills as far as we could go. Sometimes we even went into the half-outside, which was the place between the fence and the ring of hidden pits we called the stake-blind.

It wasn’t always just the three of us. Sometimes Veso Shepherd run with us, or Haijon’s sister Lari and his cousin Mardew, or Gilly’s Ban, or some of the Frostfend Farm boys that was deaf and dumb like their whole family and was all just called Frostfend, for they made their given names with movements of their hands. We was a posse of variable size, though we seemed always to make the same amount of noise and trouble whether we was few or many.

We was chased away by growers in the greensheds, shepherds on the forward slope, guards on the lookout and wakers at the edge of the wold. We treated all those places as our own, in spite of scoldings, and if worse than scoldings come we took that too. Nobody cut us no slack rope on account of Haijon’s family, or Demar’s being maimed.

You would think that Haijon, being who he was and born to who he was, might have put some swagger on himself, but he never done it. He had other reasons for swaggering, besides. He was the strongest for his age I ever seen. One time Veso Shepherd started up a row with him – over the stone game, I think it was, and whether he moved such-and-such a piece when he said he didn’t – and the row become a fight. I don’t know how I got into it, but somehow I did. It was Veso and me both piling onto Haijon, and him giving it back as good as he got, until we was all three of us bloodied. Nobody won, as such, but Haijon held his own against the two of us. And the first thing he said, when we was too out of breath and too sore to fight any more, was “Are we going to finish this game, or what?”

My boast was I was fastest out of all of

us, but even there Haijon took some beating. One of the things we used to do, right up until we went Waiting and even once or twice after, was to run a race all round the village walls, starting at the gate. Most times I won, by a step or a straw as they say, but sometimes not. And if I won, Haijon always held up my hand and shouted, “The champion!” He never was angry or hurt to lose, as many would of been.

But of course, you might say, there was a bigger race where his coming first was mostly just assumed. For Haijon was Vennastin.

And Vennastins was Ramparts.

And Ramparts, as you may or may not know, was synced.

That’s what the name signified, give or take. If you was made a Rampart, it was because the old tech waked when you touched it. Ramparts got to live in Rampart Hold and to miss their turn on most of the share-works that was going on. But we relied on them and their tech for defending ourselves against the world, so it seemed like that was a fair thing. Besides, everyone got a chance to try out for Rampart, didn’t they? Somehow, though, it was always Vennastins the old tech waked for and answered to. Except for one time, which I’ll tell you of in its place. But the next thing I’ll tell is how Demar come to be Spinner.

3

From when I was ten Summers old to when I was twelve, Lari Vennastin had a needle that she kept as a pet. She fed it on stoneberries and rats taken out of traps. She even give it a name, which was Lightning. She shouldn’t of been let to do it, and certainly nobody else would of been, but Ramparts made the law in Mythen Rood or in this case kind of forgot to.

The needle was only a kitten when Lari found it, and crippled besides. Something had bitten it and took off most of its foreleg. Then the same something must of spit it out or flung it away, so it fell inside the fence. You might of thought it had fell out of a tree except of course that was all cleared ground up there by the fence and any trees that tried to root in would of been burned.

The needle was just lying there, not moving at all except that you could see its chest going up and down as it breathed. Haijon lifted up his boot to tread on it, but Lari called out to him to let it be. She carried it home and tended to it, and somehow it lived. And it kept right on living, though there was plenty of arguments in the Count and Seal to put it down. Ramparts was hard to argue against, and Lari was the sweet and savour of her mother’s life.

Fellside

Fellside The Girl With All the Gifts

The Girl With All the Gifts The Book of Koli

The Book of Koli The Boy on the Bridge

The Boy on the Bridge Someone Like Me

Someone Like Me